Products like cars and watches are often marketed as sleek, classy and reliable. But according to new U of T research, there may be an unconscious appetite among consumers for them to convey dominance.

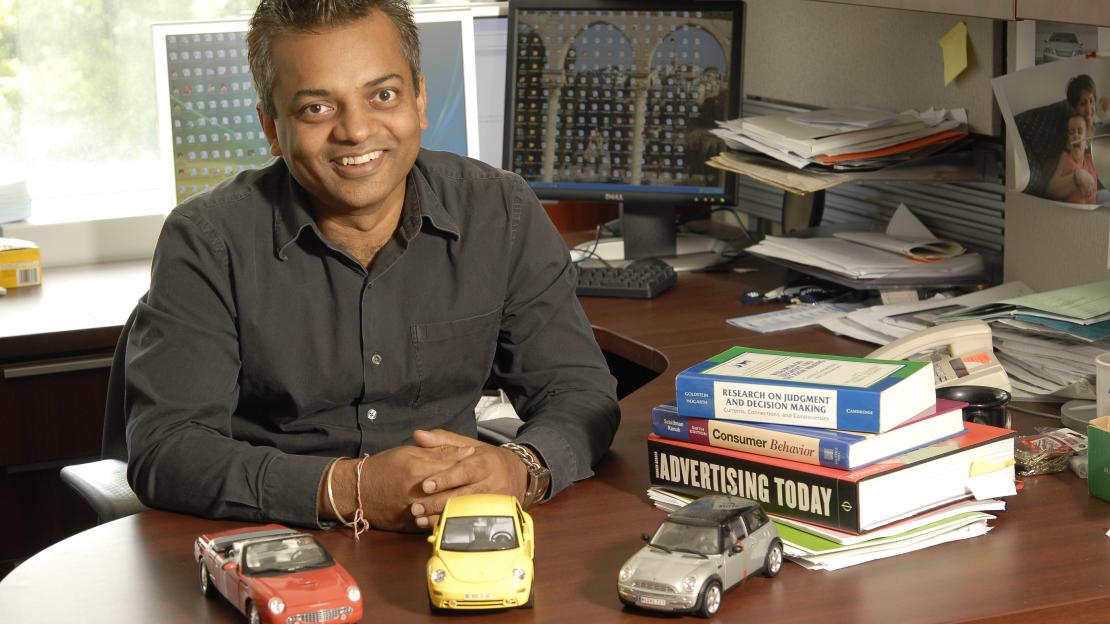

“If these products are used in situations where you’re competing with someone else, the goal may be dominance,” says Pankaj Aggarwal, a marketing professor in U of T Scarborough’s Department of Management and the Rotman School of Management.

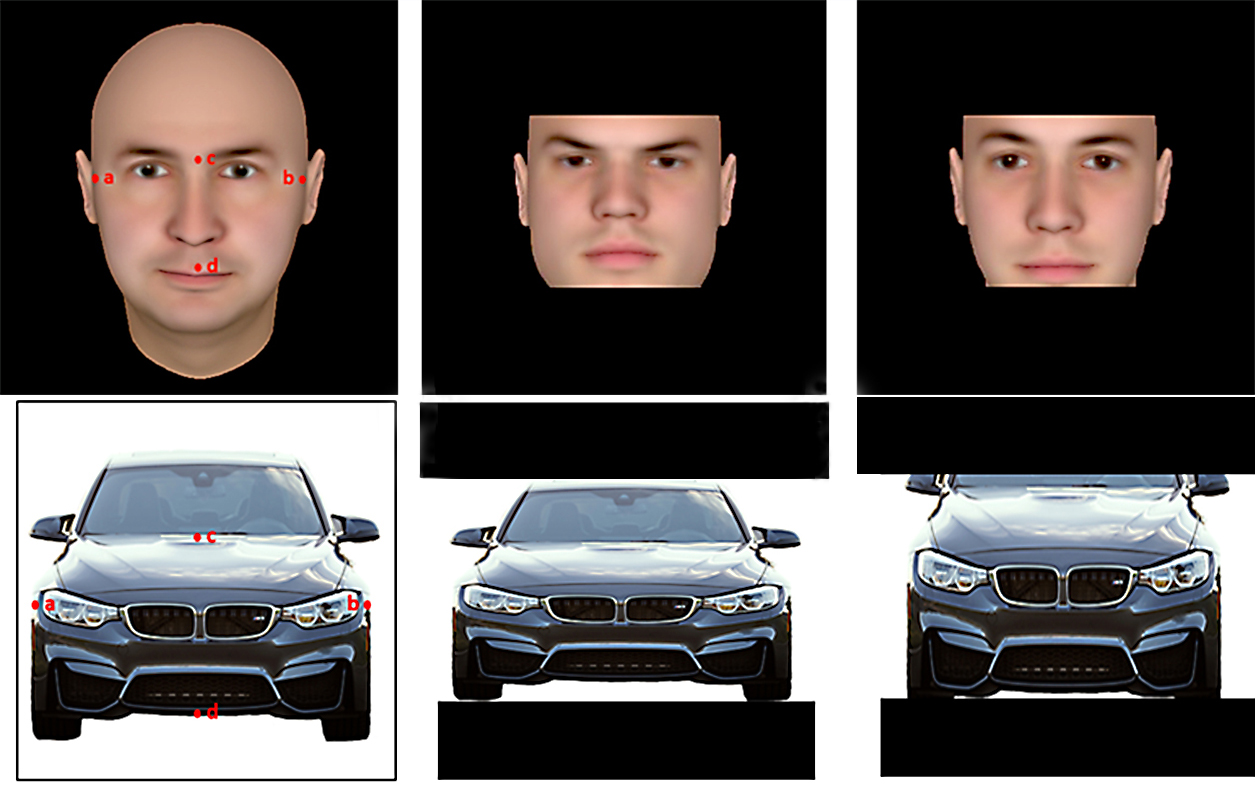

For a variety of reasons people are averse to dominant-looking faces, which tend to be wider says Aggarwal, who authored the study along with Professor Ahreum Maeng from the University of Kansas. In fact, a face with a higher width-to-height ratio is an evolutionary cue indicating dominance.

Using the notion of anthropomorphism, the idea of attributing human traits to non-human entities, the researchers wanted to see if people would also read dominance cues from products.

“We found that these preferences flip in certain situations,” says Aggarwal, whose past research has looked at the benefits of using anthropomorphism in promoting social causes.

“While people don’t want to interact with dominant human faces, we found they prefer it in certain products when their goal is dominance.”

Across five experiments, participants were asked to look at various photos of human faces that varied from low width-to-height-ratio (narrow) to ones with a higher ratio (wider). They then looked at photos of products with designs that resemble a human face including clocks, watches and cars.

The researchers then evaluated product preference in two scenarios – in preparing for a business negotiation and meeting a former bully at a high school reunion. They found in those situations people preferred the product with a more dominant-looking face.

“When it comes to a dominant-looking product face, they really like it,” says Maeng. “It’s probably because people view the product as part of themselves and they would think, ‘it’s my possession. I have control over it when I need it, and I can demonstrate my dominance through my product.”

The effect was strong when using the products in a public as opposed to a private setting, and was also less desirable in situations where dominance was not a consideration, like meeting with friends.

So what lessons are there for product designers, marketers and consumers?

For one, Aggarwal says designers may want to look beyond just aesthetics and functionality to also consider how the product represents certain traits like dominance or warmth.

“With cars, some may find it useful to convey dominance, but for others like healthcare products you may want to signal the complete opposite trait,” he says.

“You may want to be aware how the width-to-height ratio has implications for how people want to be perceived.”

There are also implications for pricing. Aggarwal and Maeng looked at more than 530 cars models sold in a given year and found that a one per cent increase in ratio led to a $250 increase in price.

“Ratio is important,” says Aggarwal. “It’s not necessarily size – cars can be the same size, but if the ratio is bigger, like a wider grill or headlights, that’s where you see the effect.”

The study, which received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and an A.F.W. Plumptre Award, is published in the Journal of Consumer Research.