A new U of T Scarborough study finds that mothers who show increased brain activity when they see infant faces while pregnant, report stronger bonds with their babies after birth.

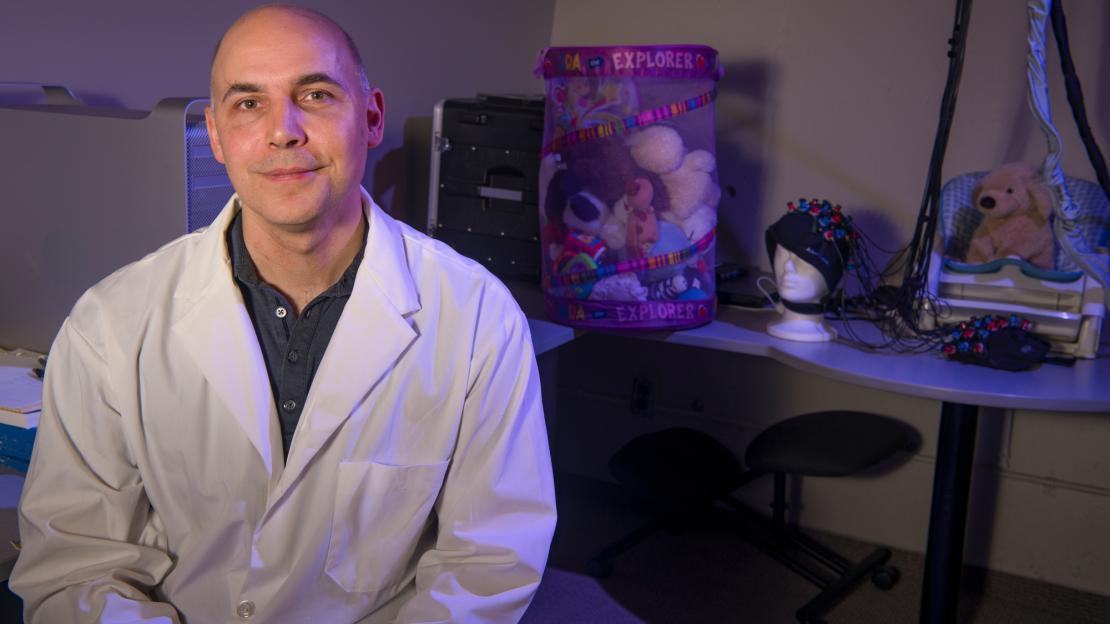

“Our findings support the idea that over the course of pregnancy and early motherhood, the responses in the brain to infant facial cues actually change,” says David Haley, associate professor of psychology and director of the Parent-Infant Research Lab at U of T Scarborough.

“We found that some mothers showed more marked changes than others, and this variation is associated with reports of the strength of their emotional bonds with their babies.”

While past research suggests the transition to motherhood triggers structural changes in the brain that may help with mother-infant bonding, most studies focus on the postpartum period. Haley’s is the first to look at whether functional changes in mothers’ brains during and after pregnancy are related to mother-infant bonding.

When responding to infant facial cues, the researchers observed increases in electrical activity in the part of the brain responsible for attention processes that occur within a fraction of a second.

Haley, who is the lead author of the study, says these early attention processes help us tune in to significant visual stimuli that may signal rewards or threats. For example, giving enhanced attention to a lion in the grass or a cute baby in a crib may be equally important for survival.

“This goes to show that mothers are increasing their cortical receptivity, but what’s fascinating is that this increase seems to predict behavioural receptivity to their infants,” he says.

While past research suggests the transition to motherhood triggers structural changes in the brain that may help with mother-infant bonding, most studies focus on the postpartum period. Haley’s study is the first to look at whether functional changes in mothers’ brains during and after pregnancy are related to mother-infant bonding.

The study involved 39 pregnant women, ages 22 to 39, from various ethnic and educational backgrounds. Each of the women visited the lab twice, once in their third trimester and again three to five months after giving birth. During the visits, the women took part in a face-processing task where they were shown images of sad and happy infant and adult faces while their brain activity was measured using electroencephalography (EEG).

One surprising finding from the study is that a significant change in receptivity to infant facial cues was seen only among some mothers between pregnancy and the postnatal period.

“That was unexpected,” says Joanna Dudek, who earned her PhD in Haley’s lab and who co-authored the research.

“It suggests the transition from pregnancy to motherhood is not a period of universal adaptive change in receptivity to infant facial cues.”

The mothers in the study were all shown unfamiliar infant faces, so Dudek says it’s unknown whether mothers who did not show a change in receptivity would do so if they were shown their own infants' faces postnatally.

Haley says understanding the emotional and cognitive networks in the brain underlying mother-infant bonding is crucial because the early relationship between mothers and infants is widely considered of key importance to childhood development.

“There’s been a lot of research on the importance of forming close mother-infant bonds, but little is known about how this bond may start developing in the first place,” he says.

Why some mothers experience a change in receptivity while others don’t remains an open question. Haley says the mental and physiological health of the mother could play a role, pointing to recent research that shows stress can dampen and inhibit the neural responses to infant facial cues.

Unpacking why this happens is an important next step for the research along with measuring whether there’s a change in mothers’ neural receptivity to infant facial cues beginning earlier in pregnancy.

There’s also good news for mothers who don’t show an increase in receptivity to infant facial cues. Past research has shown that people can train to increase their attention bias.

“There are studies showing that mothers can do it with infant stimuli, so it’s possible that mothers could learn to increase their attention bias towards their infant,” he says.

He adds whether attention increases gained through training can predict maternal bonding in the postnatal period is also a topic for future research.

The study, which received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), is published in the journal, Child Development.