Luna Yu is passionate about not wasting food.

“I was taught at an early age by my grandparents never to waste food since it was throwing away the hard work of farmers and food producers,” says Yu, a recent graduate from the Master of Environmental Science program at U of T Scarborough.

“More than $1 trillion worth of food is wasted globally every year. What we’re able to do is take this waste and turn it into something of higher value.”

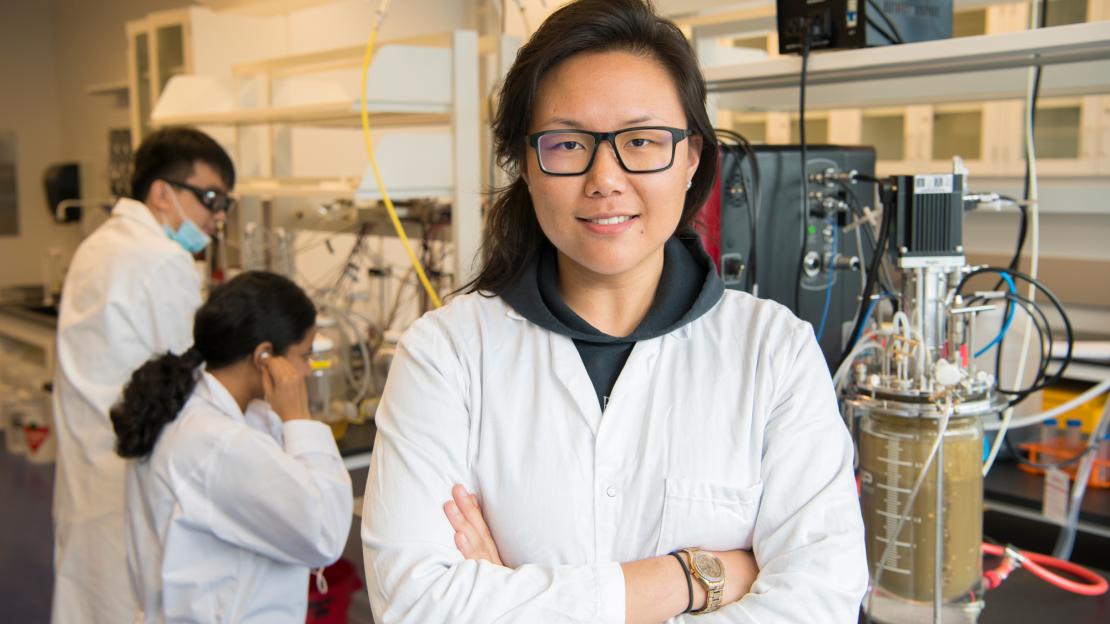

It’s no wonder that passion led Yu to team up with a talented group of scientists and engineers — many of whom are U of T students or alum — to form Genecis. The company uses recent advancements in biotechnology, microbial engineering and machine learning to take food destined for landfill and convert it into high quality, fully biodegradable plastics.

Food waste is a significant environmental issue in North America, explains Yu. In the United States roughly 55 million tons of food is thrown away annually. Once that food hits landfill it generates methane, a greenhouse gas that’s 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide. In fact, it’s estimated that 34 per cent of methane emissions in the U.S. alone are caused by food waste.

“We feel that by using synthetic biology create high quality products out of this organic waste in a cost-effective way – while also mitigating the effects of plastic pollution – is really the way of the future,” she says.

Though only in her early 20s, this isn’t Yu’s first foray into entrepreneurship. She has more than six years’ experience, first at a start-up software company as an undergrad before moving to another start-up that converted restaurant food waste into biogas.

It was there that she met several talented engineers, learned about the microbiology of converting discarded food into other materials, and discovered a valuable lesson in the economics of re-using food waste.

“Converting food waste into biogas is not only a time-consuming process, the end product is fairly low value,” she says.

It was shortly after this experience that she connected with a fellow environmental science student in The Hub, U of T Scarborough’s entrepreneurial incubator, to figure out what else could be made from food waste.

“We looked at different types of bio-rubbers and bio-chemicals before landing on PHAs. We felt it had the biggest market potential.”

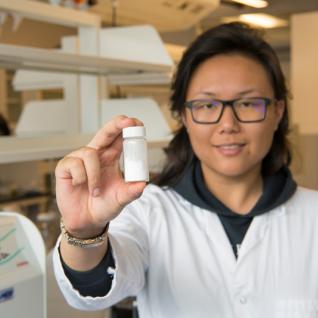

A reusable, biodegradable form of plastic

PHAs, or polyhydroxyalkanoates, are a type of polymer produced in nature by bacteria that have many benefits over other forms of bio-plastics. For one, it can be a thermoplastic, meaning it can be easily moulded and remoulded into different products. Another benefit is that, unlike many other forms of bio-plastics, it won’t ruin the recycling process.

“Many people throw bio-plastics into the recycling bin rather than the compost, but if it’s not a thermoplastic, it can’t be remoulded,” says Yu.

“This disrupts the physical properties of new recycled products — they will end up falling apart.”

PHAs won’t cause this problem if it accidentally ends up in recycling bins, which makes it much easier for waste management companies to handle.

But what really sold Yu on PHAs is the fact that it’s fully biodegradable. PHAs degrade within one year in a terrestrial environment, and fewer than 10 years in marine environments. Meanwhile, synthetic plastics can take hundreds of years to degrade in similar environments.

Given its superior physical properties and the process it takes to create, Yu says Genecis’s PHAs are best suited for higher-end products like toys, flexible packaging, 3D-printing filament and medical applications including surgical staples, sutures and stints.

“The PHAs we create can be used to make pretty much anything, but it makes the most economic sense to use it in higher-quality, multi-use products,” she says.

While PHAs have been in the market for the past two decades, most come directly from corn and sugarcane crops. Yu explains that the process Genecis uses to create its PHAs is much cheaper because they avoid the expenses required to acquire their feedstock.

Three-step process

Genecis uses a three-step process to produce its PHAs, explains Michael Williamson, the company’s head of mechanical engineering and U of T engineering grad.

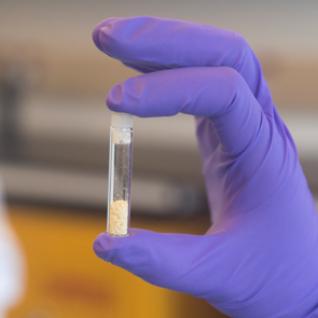

First, they use a mixture of anaerobic (without oxygen) bacteria that breaks down the food waste into volatile fatty acids, similar to how food is broken down in our stomachs. Next, the fatty acids are added to a mixed culture of aerobic (with oxygen) bacteria that are specially selected to produce PHAs in their cells. Finally, they use an extraction process to break open the cells, collect and purify the plastic.

The process takes less than seven days from getting the food waste to having the purified plastic — making biogas, on the other hand, takes an average of 21 days. When the company opens its demonstration plant later next year, it will be able to convert three tonnes of organic waste into PHAs weekly.

While the process used by Genecis works for pretty much all types of food, some foods like simple carbs and proteins can be more efficiently converted, says Yu.

The company currently has two locations — their main lab in U of T’s Banting and Best Building, in the heart of Toronto’s Discovery District, and the other in the Environmental Science and Chemistry Building at U of T Scarborough, which is responsible for research and development.

U of T start-up

In their downtown lab they work with pilot-scale bioreactors, and are continuing to scale up their operations with an industry partner to a demonstration plant by the end of next year. Meanwhile, their facility at UTSC houses smaller bioreactors that are used to help optimize their production process.

“We’re fine-tuning things to figure out the best conditions to operate our bacteria cultures,” says Vani Sankar, Genecis’s head of biotechnology and a postdoc at U of T Scarborough. “This includes what combinations of temperature, pH and amount of food will give us the best yield.”

In less than two years of operation, Genecis has already won more than $330,000 in prize money from start-up competitions. Yu says the support, guidance and mentorship they’ve received from the Hub, the Creative Destruction Lab, and the Hatchery, a start-up accelerator at U of T Engineering, has also been instrumental in their growth.

“I can’t say enough about the support I received from the Hub. It’s a great place to go for any students interested in starting their own company. I formed great partnerships with other students there and the mentorship I received was second to none,” Yu says.

As Genecis aims to ramp up production, Yu says this support and the lessons learned from her work in other start-ups will be invaluable.

“Our goal is to create the highest value from organic waste,” says Yu, adding they’ve cultured and isolated hundreds of species of bacteria that currently don’t exist in databases.

“Soon we will be able to synthesize speciality chemicals and other materials from organic waste, all at a lower cost than traditional production methods using synthetic biology,” she says.

Those specialty chemicals can be used in a range of products including those found in cosmetics and the health and wellness industry, says Yu. “It’s a really exciting time for us.”