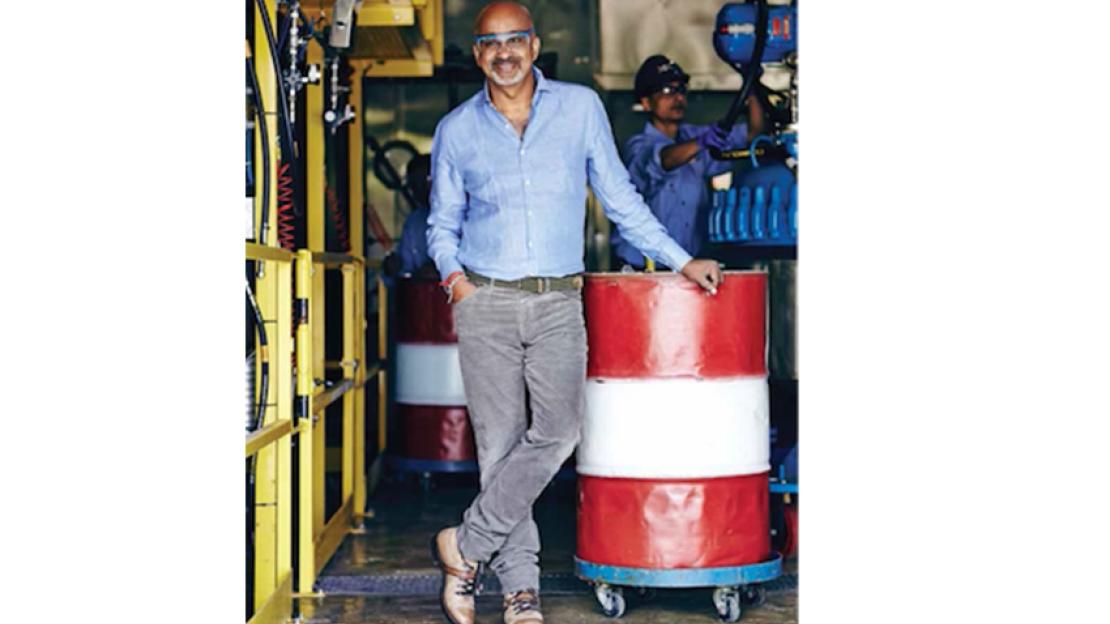

If you meet Ravi Gukathasan (U of T PhD, 1986; UTSC BSc, 1982), he is bound to strike you as a joyful person—bright-eyed, high energy, full of smiles and laughter. In October 2013, he had every reason to be joyful about his nearly three decades in business. His Scarborough-based company, Digital Specialty Chemicals (DSC), was booming—best year ever. He had a great, highly educated staff with a very low attrition rate and was poised to expand. But, he says, “I was miserable— totally unhappy.”

He felt everything he was doing was wrong. “I asked myself, what am I building in this corporation? We were like every other corporation, just building it to make money. I could have started crying.” It’s not as if he hadn’t been generous to his employees. In 2008 he had transferred 12.5 per cent of the company to his staff—a share worth millions—for a price of just $12 per person.

“That was my guilt,” he says. “I thought that was how I was going to save my soul. I never regretted it, but I was still miserable.”

His October crisis was the beginning of a journey. In the ensuing months, he would learn about a business concept called the dual bottom line, and start a small revolution at DSC. Dual bottom line means that employees’ human development is as important as the company’s financial results. Gukathasan says he stood in front of his 60-plus employees and apologized. “I told them, ‘For 28 years, I have spent over $20 million in capital investment in this company, but in terms of human development, I haven’t spent even $1 million.’"

The basic idea is that an organization becomes all about learning and education. Employees, even at ground level, learn in detail about the organization, including financial information and what their colleagues do. Then they apply that learning to how they work and make their own decisions about how to meet the company’s goals. It doesn’t stop there: they are also expected to become better people—more cooperative, more generous, more developed. Performance reviews include both financial and human metrics.

“I call it emancipation of the people. I’m not exaggerating,” says Gukathasan. “They are truly free. Every task is based on learning and knowledge creation—they have to learn. We truly believe it sets the stage for them to get liberated and become a better human being.”

The old way, he says, involved top-down command and control. “Our operators were just a pair of hands.” The new way requires everyone to be a leader as well as a servant, he says. Gukathasan knew not everyone could handle this kind of change and was not afraid to deal with that. Late last year, he swept out nine key executives, including his chief financial officer and his director of sales and marketing. “I needed a new mentality to go forward.”

As the process continues, Gukathasan hopes to add a third bottom line: environmental sustainability, no small matter in a chemical company. The firm already has high standards, using sophisticated scrubbers that get rid of harmful waste and emissions, but he feels it can do even better.

Gukathasan has also beautified the neighbourhood, creating a public park on half of DSC’s four-acre property on Coronation Drive. In the future, he hopes to help improve life in the surrounding community. “My dream,” says Gukathasan pointing to the north side of the long block, “is to own this whole street.”

Where do such visionaries come from? Gukathasan’s story runs parallel to that of many other Tamils who have settled in Canada, with a high concentration in Scarborough. He grew up just outside Jaffna in northern Sri Lanka, where his parents were civil servants. Early on, his father recognized the growing tensions between Tamil separatists and the Sinhalese majority. In 1974 the family moved to England, where the young Ravi attended high school and became a lifelong fan of the Liverpool Football Club. But 1970s Britain was not always a happy place for visible minorities, and when his father asked if he’d like to attend university in Canada, he was ready to jump. The family re-settled in northern Scarborough. Gukathasan, always good at science, was accepted at what was then U of T’s 13-year-old Scarborough College. He says he was one of only two Tamil students.

He tried some art courses, but Gukathasan quickly doubled back to science, where Professor R.T. Hemmings instilled in him a love of inorganic chemistry. “My goal was to get ‘Dr.’ in front of my name,” he says with a chuckle. “My parents wanted me to do medicine, but I didn’t have the discipline. So I went for a PhD in chemistry.”

Gukathasan completed his PhD in 1986 at U of T. But he had also acquired a taste for business, from working with a friend to sell T-shirts to university clubs. Then, as luck would have it—and Gukathasan is a big believer in luck—a prominent Toronto educator and businessman, Harry Giles, asked U of T’s chair of chemistry if he knew someone who could help him solve a problem with a chemistry-related venture. The chair said, “Talk to Ravi. He’s an entrepreneur.”

That relationship led to start-up funding for DSC in 1987, with Gukathasan offering highly specialized chemical products that could be scaled up quickly from laboratory amounts to commercial volumes and delivered on a tight deadline. Today they are used in everything from pharmaceuticals to electronic chips. Through it all, Gukathasan’s chief operating officer has been his wife, Dr. Caroline Schweitzer (BSc, 1982), a fellow U of T and Scarborough College grad whom he met at the downtown campus. They have two teenaged children.

As DSC grew to its current revenue level of nearly $25 million a year, Gukathasan plowed some of the profit into art, including Aboriginal carvings that are on display in the lobby. He also created a mini-park by planting 74 trees on the barren property he acquired in 2000. A large, polished memorial stone sits at the mini-park entrance. It is carved with the names of the 135 soccer fans who died in two notorious 1980s stadium riots involving Liverpool FC. Gukathasan sees these riots—Heysel and Hillsborough— as terrible failures on the part of the police. And he’s added the names of the two Toronto people who died in the Danzig Street mass shootings in 2012. “I felt, how could I do this without acknowledging our own neighbourhood?”

Gukathasan has donated $500,000 to UTSC to support the study of Tamil culture and also a DSC scholarship.

If he realizes his vision of buying up a long stretch of Coronation Drive, he hopes to consult with UTSC environmental experts on how to improve the land.

“By bringing nature back,” he says, “can we renew a dying urban community? My answer is ‘Yes’.”

For now, though, he is focused on turning his company into a true dual-bottom line operation, a process that took flight last year after he met U.S. management guru Kazimierz Gozdz at a Harvard conference. The conference was on deliberately developmental organizations. It was there, says Gukathasan “that I learned for the first time why I was miserable.”

Gozdz is now advising the company on what Gukathasan expects will be a five-year process. The time frame roughly corresponds to his aggressive schedule for making DSC a $100-million company, boosted by a recent injection of funding from Intel Capital, a division of the chip-making giant. Gukathasan believes DSC will perform much better in its new form, but says this is not his motivation. On the contrary, “I will even slow down if I have to, in order to help the dual bottom line.”

As the transition takes hold, DSC employees have worked out a new schedule, converting the operation from a seven-day to a five-day week. “Why should only the executives get the weekends off?” asks Gukathasan. Meetings have also been transformed. “Everybody talks. Everybody speaks their mind,” he says. “There are no politics, no corridor conversations. We have meetings as a true community.”

Gukathasan has come a long way since he sold T-shirts to his fellow students. “I truly believe you can inspire people, and inspiration is not based on a single bottom line,” he says. “It’s a collective, holistic perspective. You can do things differently.”