By connecting the many fragmented trails throughout Toronto’s east end, every corner of Scarborough could be reached by foot or bike, creating potentially the most comprehensive network of off-road paths in the world.

A new report proposes a network of paved, landscaped trails — referred to as greenways — running through Scarborough’s extensive parks and public land. The trails would connect to the area’s major hubs and transit stops, and be less than a kilometre away from 93 per cent of Scarborough residents.

“There are very few greenway networks in the world that would be as extensive and as beautiful as this one,” says Andre Sorensen, co-author of the study and professor in the department of human geography at U of T Scarborough. “One of the exceptional things about our proposal is that this does not require any land expropriation, this is all land that's in public ownership.”

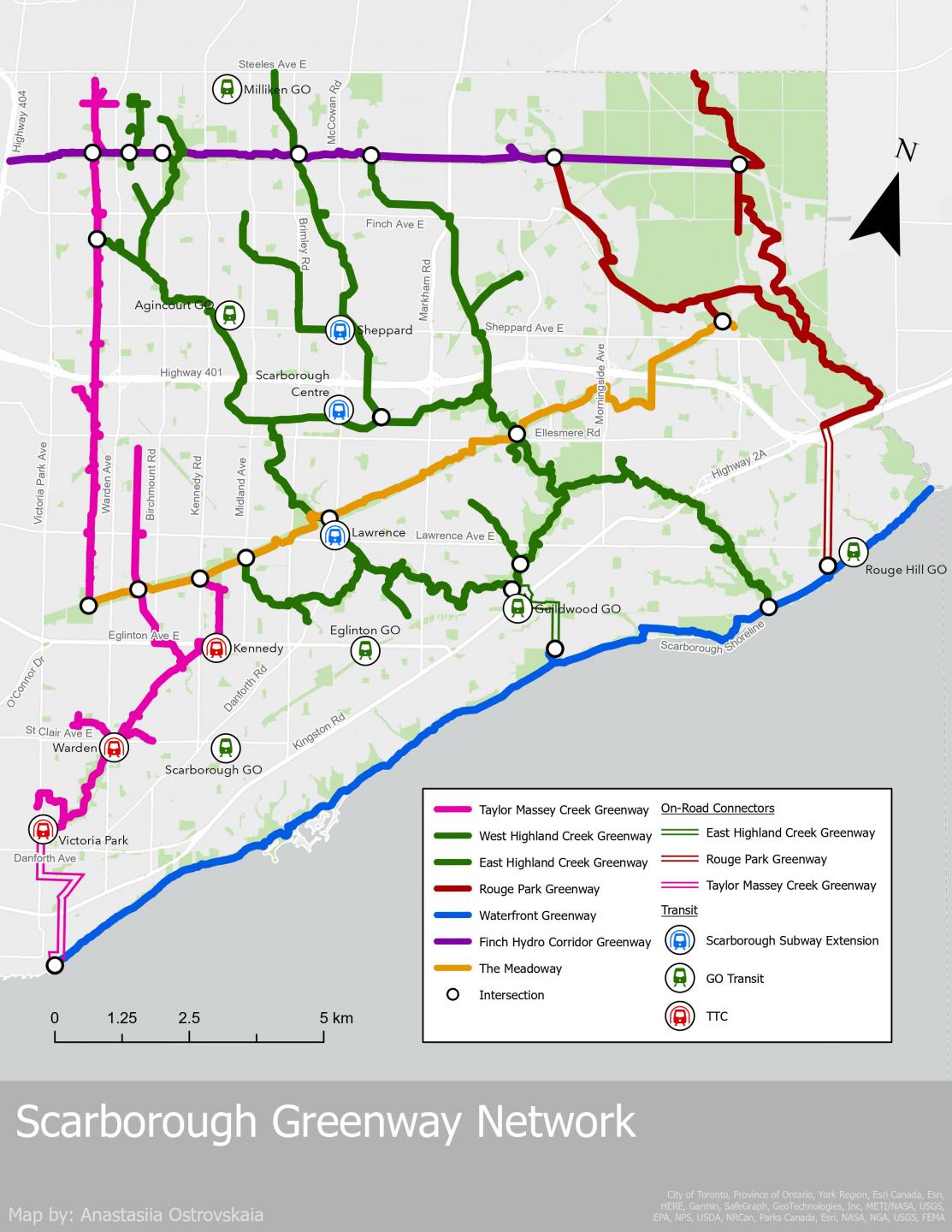

More than half of the network already exists in short, disjointed trails across Scarborough. Those routes would be revamped and linked together to create three greenways running north to south and three running east to west. Plans also include connections to the upcoming greenway between Rouge Park and the Don Valley, dubbed the Meadoway, and converting the soon-to-be-decommissioned Line 3 into an elevated path, similar to New York City’s High Line.

“The Meadoway trail should be seen as just the down payment on a truly great greenway trails network,” says Sorensen, an expert on urban planning.

Most trails would cut through parkland and could be built quickly and easily; others must overcome obstacles such as Highway 401, the Scarborough Bluffs and busy railway tracks. It would take some new infrastructure, though the report suggests interim routes that would help the network come to life while larger construction projects are in the works.

“Making it easier to bicycle and walk will lead to more local active transportation and will help to support local small businesses,” Sorensen says. “If this network is created, condo and office developers will be able to advertise that their development is on this trail network. This could become a major tourist attraction.”

The pressure is on as the public land the network needs is at risk of privatization. Several key corridors have already been sold off, and Toronto expects to add one million residents in the next 30 years. Development is expected to increase in the east end as projects such as the Eglington Crosstown and the Scarborough subway extension arrive.

“We believe it is essential that the city design and approve a plan for a connected network of off-road trails before large-scale development really starts happening in Scarborough,” Sorensen says.

Almost half a million trips made daily in Scarborough are less than five kilometres, yet 70 per cent of them are travelled by car. It’s easy to understand why — and why Scarborough shoulders a disproportionate amount of the city’s pedestrian injuries and deaths from traffic accidents. Few roads have dedicated cycling paths, and many operate more like highways, with high speed limits and intersections meant to usher vehicles through as quickly as possible.

But Scarborough’s layout is inadvertently perfect for car-free travel. Its suburbs surround huge corridors of public land originally dedicated to hydroelectric infrastructure. And unlike in downtown Toronto, many creeks and streams were left above ground and lined with concrete to create drainage ditches, which the report calls the worst possible approach to stormwater management. These waterways tend to flow into one another, on more public land about 20 metres wide.

The report proposes transforming those channels into trails bordered by wetlands, ponds and trees. Removing the concrete and adding natural barriers to slow and absorb rainwater, particularly in the upper reaches of the Highland Creek area, would help prevent flooding downstream.

A major policy priority for the City of Toronto is to create ways to get active while travelling. Last year, Sorensen co-authored a report that accused the city of failing to build the infrastructure needed to make its goal a reality in Scarborough. That paper recommended a series of on-road paths, though Sorensen says the greenway network would likely see much less resistance from drivers.

“One advantage of this proposed network is that it is expected to improve cycling and walking infrastructure without disrupting traffic,” Sorensen says. “There's not many people actually opposed to off-road paths, because they’re not taking away traffic lanes.”