Three U of T researchers – including two from U of T Scarborough – are behind a new technology that was named today as the winner of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s new Analytical Division Horizon Prize, the Sir George Stokes Award.

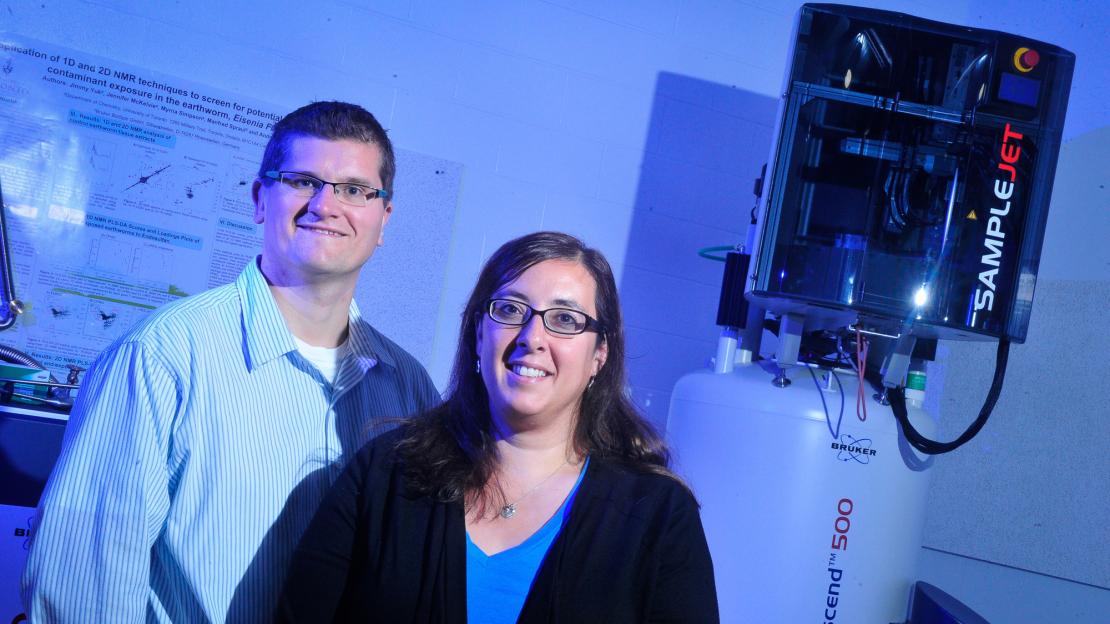

Professors Andre Simpson and Myrna Simpson from the department of physical and environmental sciences, and Professor Aaron Wheeler from U of T’s department of chemistry, were part of an international collaboration that integrated digital microfluidics and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy for the first time.

The technology promises to change the landscape of analytical chemistry with a wide range of uses, from an automated discovery platform in synthetic chemistry, to automated water toxicity testing.

Digital microfluidics (DMF) allows droplets to be moved, mixed and dispensed on a set of electrodes at a micro scale. These processes can be automated with software.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical tool that studies molecular structure and interactions. One of its limitations is its ability to analyze small sample sizes. NMR microcoils were created to address this challenge.

By combining these two technologies, DMF-NMR allows for the first time the interfacing of droplets with microcoils in a high-field NMR spectrometer.

The Horizon Prizes celebrate the most exciting, contemporary chemical science at the cutting edge of research and innovation. These prizes are for teams or collaborations who are opening up new directions and possibilities in their field, through ground-breaking scientific developments.

“We are completely honoured and humbled to receive this award,” says Andre Simpson. “It was so much fun working on this project, as it brought together scientists from a diversity of fields and across industry and academia. We all found it extremely rewarding, developing technology with potential applications across a range of disciplines, from chemical synthesis to medical diagnosis.”

Once developed and tested, it is hoped that the research will eventually lead to knowledge of the most problematic stressors impacting environmental and human health, in turn improving monitoring, targeted remediation and prevention as well as informing global environment and health policies.

Using the technology as a chemistry discovery tool also opens up the potential to create new chemicals, new cancer drugs and new plastics, among countless other possibilities.

This story originally appeared on U of T’s department of chemistry website.