Is there such a thing as plant racism? To many, that question is nonsensical, but to Leslie Chan, associate professor at the Centre for Critical Development Studies at U of T Scarborough, the question is not whether it exists, but how best to address the racism inherent in how science categorizes plants. (And animals, diseases and sociological issues.)

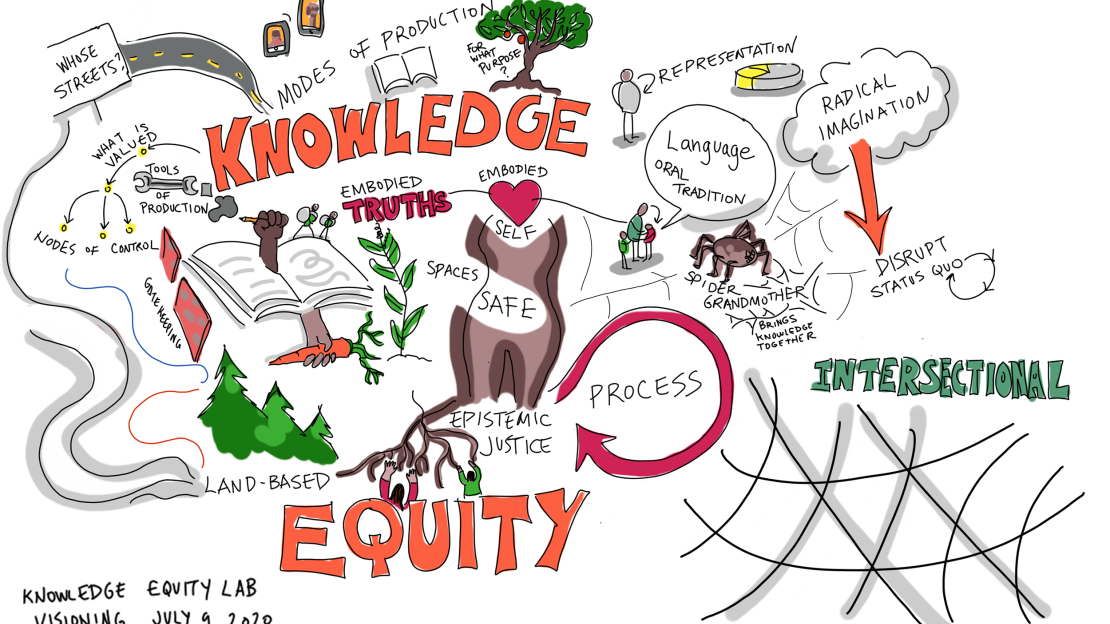

Chan’s solution, the Knowledge Equity Lab, launches this week, and is already home to dozens of collaborations worldwide. Each of these will address what he terms “scientific racism” — the marginalization of systems of knowledge and ways understanding the world and that are not central to the West, and its prevailing system of capital and finance.

Consider the treatment of the Kenyan vegetable called jute mallow. Its green, fleshy leaves have been eaten in Africa and Asia for at least 2,000 years. (Pliny the Elder recorded that the Ancient Egyptians liked it.) High in calcium, potassium, iron, sodium, phosphorus, beta-carotene, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin and ascorbic acid, it is used in soups, salads and stews. It has long been considered a staple of the Kenyan diet, according to Professor Mary Abukutsa-Onyango, a professor at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, whose mother liked to cook with it when the professor was a child.

After more than a decade of research, Abukutsa-Onyango wrote a scientific paper on the jute marrow and other African indigenous vegetables, and how these legumes could replace global monoculture and be used to address the nation’s problems with child malnutrition, poverty, and food security. She submitted her research paper to several international journals. “They didn’t recognize my work, not because it wasn’t good, but because they regarded these plants as weeds.”

Abukutsa-Onyango published her paper in a local journal, and Chan distributed it on the publishing platform Bioline International. The global, open-access platform, which he co-founded, aims to address the systemic inequity that exists in scientific publishing, whereby diseases, methodologies, technologies, plants, and animals that are less known to the West are marginalized or ignored.

The world of scientific publishing privileges knowledge that comes out of the Western institutions,” Chan says. “It devalues knowledge that come out of the former colonies, because they are seen as places of backwardness.

Since the early 2000s, there have been a growing number of research papers on the problem of scientific racism, and how it distorts what is supposed to be a pure and unbiased enterprise. Bioline International publishes peer-reviewed papers from institutions in the developing world and reaches millions of readers worldwide each year. The Knowledge Equity Lab will be a research and teaching space that supports researchers doing similar work. The lab will also promote collaborations with community leaders, Indigenous scholars, farmers, artists, students, and others who may have knowledge about a specific area affected by systemic bias, although are not part of the academic system. Some of these initiatives are student driven, such as the Open Praxis Forum; others are focused on international collaborations, such as the Open and Collaborative Science for Development Network; others are focused around community partnerships, such as the Community Knowledge Learning Hub.

This is particularly important in today’s pedagogical environment where climate change is causing rapid environmental disruption. The damage to fragile ecosystems necessitates seeking partners beyond the traditional academic system to what Chan calls “knowledge holders,” people who understand the realities on the ground, and what adaptations are necessary.

“Some of our collaborators are looking at indigenous plants that are more drought resistant,” Chan explains. “The sustainability knowledge exists in many communities. If we really want to think about how to reduce climate change, we have to learn from our community partners.”