U of T is stepping up efforts against anti-Black racism and moving toward greater inclusion

I was awake when the video began to circulate on Twitter. I saw the outcry of Black voices online and knew another one of us had been taken.

On May 25, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black American man, was killed by a white police officer. Other officers joined in pinning his unconscious body to the ground.

As I often do when I see this kind of news in my feed, I thought of my brother. I thought of my dad, my cousins and my uncles. I got through only a few heart-stopping moments of the footage before shutting down my computer and crawling under my covers.

Earlier that day, I had received news that an old family friend, like a grandmother to me, had passed away. She had contracted COVID-19 in her nursing home a few weeks earlier. In May, we didn’t know what we know now, which is that, in North America, Black and racialized communities are disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

As a Black person living in Canada, I sometimes feel overwhelmed by the evidence of how institutions of all kinds – from education to health care to law enforcement – discriminate against us, cast us as stereotypes or reinforce existing prejudices.

The effects can be deadly. George Floyd and Breonna Taylor are just two of the Black individuals who, in widely reported incidents, lost their lives to violence. There are countless others. I say their names to myself: Abdirahman Abdi, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, D’Andre Campbell. Not a week has gone by when I haven’t thought of Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Ruth Salau, a 19-year-old Nigerian-American Black Lives Matter activist killed after being brutally assaulted.

These stories, these losses weigh on our minds. They’re inescapable. Many of us wake up, rearrange our faces for Zoom meetings and compartmentalize our feelings, entering environments that may not accept us for all that we are.

So I take heart at the sight of protesters in this country, and around the world, who call for justice and the dismantling of systems that are working against racialized communities. These protesters are taking action. They call on Canadians to recognize that anti-Black racism isn’t only an American problem.

The responses to the protests give me hope. Many companies and organizations, including the university, have restated their commitment to fight anti-Black racism. As a U of T Scarborough alum and a full-time staff member, I feel privileged to have seen some of this anti-racism work up close. I am encouraged by the university’s commitment to change.

I graduated in 2017. Not one of the professors who taught me in my degree program was Black, although I remain forever grateful to the Black educators in adjacent courses and Black guest speakers who let me know I wasn’t alone.

I have felt the pressure to assimilate in order to succeed. Would I go further if my hair was straight and loose? Am I too dark-skinned to be considered for an on-camera assignment? Do people perceive a threat when I, a larger, dark-skinned Black woman with locs, walk into a room? With so few faces like mine in my program, I often asked myself this question. Many times, I felt complicit by not speaking up about racist microaggressions from instructors.

Recently, I spoke with Osaretin Obano, a fifth-year Black student at U of T Scarborough, who, like me, was never taught by a Black professor in his program. I think Obano raises the concerns of many when he says he would like to see many more Black faculty, staff and students at U of T. He also wants meaningful change in the university application process to consider a wider range of non-academic experiences. “The methodology doesn’t reflect equal opportunity,” he says.

I HAD MANY OF THESE THOUGHTS in mind in early October as I attended the National Dialogues – a first-of-its-kind discussion led by U of T that brought together leaders, faculty and staff from universities and colleges across the country to discuss how to combat anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion. Subsequent events in the National Dialogues series – which aims to address inclusion (or the lack of it), at higher education communities in Canada – will cover topics such as Indigeneity, mental health, disability and gender.

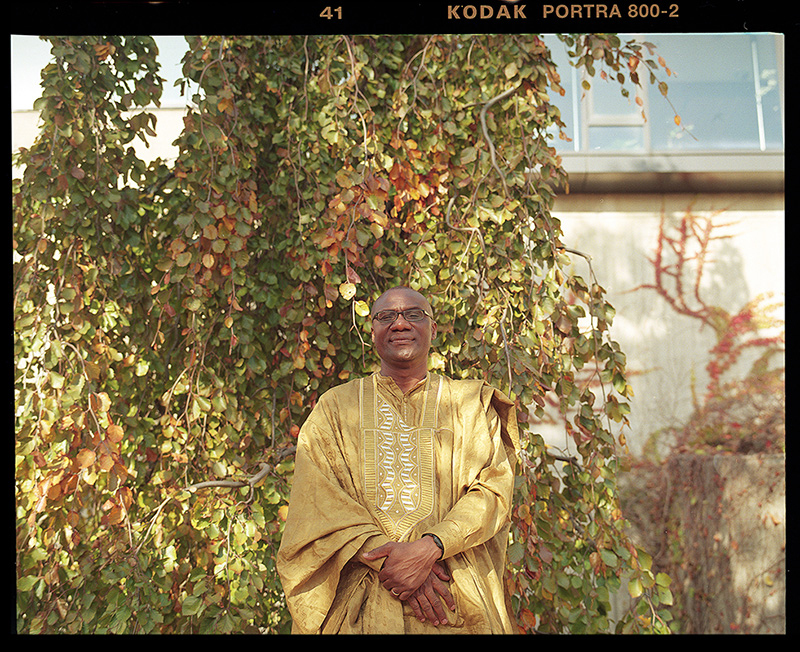

Co-ordinated by Wisdom Tettey, the principal of U of T Scarborough and a U of T vice-president, and Karima Hashmani, the university’s executive director of equity, diversity and inclusion, the initial two-day forum featured sessions that considered the diverse experiences of identities within the Black community. Many people in attendance spoke up with ideas for eradicating anti-Black racism and for what lasting Black inclusion within universities and colleges would look like.

Breaking down barriers and including others has always been important to Tettey, who was born in Ghana and is the first Black principal at U of T Scarborough and the university’s first Black vice-president. Tettey says we must be purposeful in enabling Black inclusion while at the same time trying to dismantle the pillars of anti-Black racism. “They are not necessarily the same,” he says. “We have to look at it in tandem and we have to be making progress on both fronts.”

Earlier this year, U of T Scarborough released its strategic plan, with inclusive excellence as its central theme. The document calls for a number of measures to boost equity and diversity. These include hiring more Black faculty and staff, and creating more opportunities for their advancement into leadership roles; recruiting more Black students; and changing the curriculum. “It’s not enough to say we don’t see manifestations of anti-Black racism,” explains Tettey. “Does the curriculum reflect our community? Does it tell the story of Black achievement, contributions, excellence and history?”

Such ideas will be reflected in the Scarborough National Charter on Anti-Black Racism and Black Inclusion in Canadian Higher Education. The document, to be released early in 2021, will draw from discussions held at the National Dialogues, and will serve, Tettey says, as a “compass to whether or not we are addressing this issue to the extent that is necessary.”

“My hope is that all of us will drive change in a way that is more concrete,” he says.

As the National Dialogues brought together participants from universities and colleges across Canada, U of T had already begun to elevate the issue of anti-Black racism across its own three campuses. This past September, the university established the Institutional Anti-Black Racism Task Force to capture the experiences of – and address the barriers faced by – members of its Black community.

When the task force was announced, Kelly Hannah-Moffat, U of T’s vice-president, human resources and equity, emphasized that responsibility for ending racism rested on all members of the university community. “Racism is not an issue for Black and racialized communities to address,” she said. “It is our collective responsibility to take steps to eliminate barriers and create inclusive spaces for Black students, staff, faculty and librarians.”

Does the curriculum reflect our community? Does it tell the story of black achievement, contributions, excellence and history?

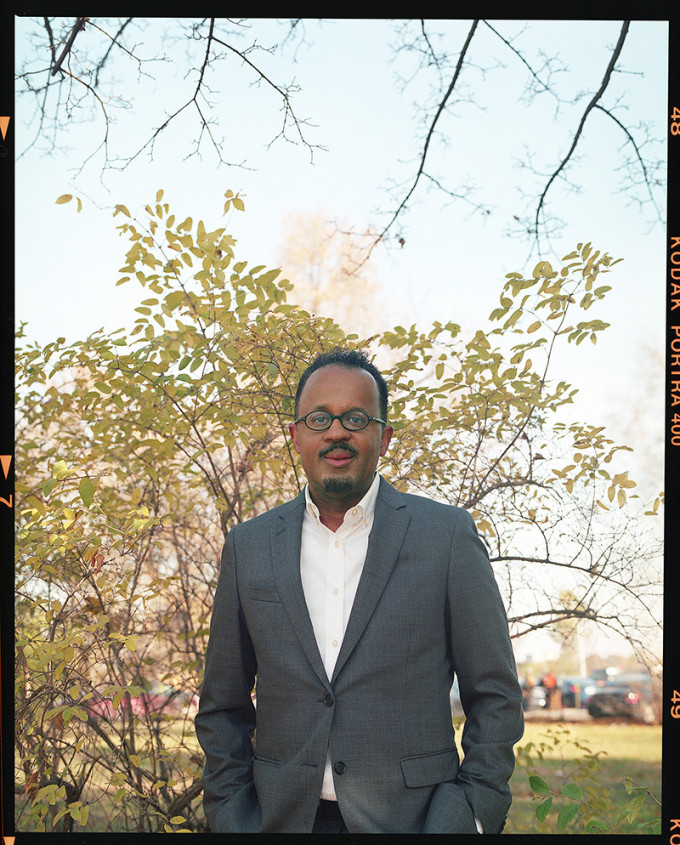

DEXTER VOISIN, U OF T’S FIRST black dean of the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, is a co-chair of the task force. He says the group is charged with addressing how anti-Black racism occurs at the institutional level and laying out ways to promote Black achievement and excellence. “Very often, we think of anti-Black racism being dependent on someone saying something or acting in particular ways, but I see it as a structural issue in how it manifests.”

Some of those manifestations dovetail with what U of T Scarborough identified in its strategic plan. These include the lack of representation in curricula, and, as Voisin describes, the presentation of Black lives and Black bodies from a “deficit, pathologic or patronizing” perspective. “When you think about the lack of Black leadership in places and positions of power across the university,” Voisin says, “that signals to Black people, to Brown people, to Asian folks, that expertise shows up in white bodies. Individuals cannot become what they cannot see.”

During the current academic year, U of T community members across the three campuses are being invited to share their ideas with the task force, which will present its recommendations for action in March.

For faculty and staff who have been doing the work – engaged in equity, diversity and inclusion at U of T – this year’s conversations have sparked hope and a renewed focus at the university. Hashmani says the societal discussion around racial injustice has given her office the chance to connect with U of T communities differently. “There is demand for this work, and we are engaged with academic divisions across the three campuses,” she says. “Our colleagues want to ensure this is prioritized.”

The university has also hosted specific events in response to the ongoing incidents of racial violence and injustice this year. In June, the U of T Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity Office hosted a series of virtual sessions – including a space for Black community members only – to gather, heal and experience restoration. They drew more more than 2,000 participants.

Those sessions were followed soon after by two online events focusing on allyship and solidarity, with conversations on what it means to operate within a culture of whiteness and Eurocentrism. “What makes me hopeful is that we are pushing in the direction of meaningful discussion and change,” says Hashmani.

To address the ongoing need to provide a sense of community and support, early in 2020 U of T Mississauga launched Black Table Talks, which connects students with Black faculty and staff. (During the pandemic, the series has continued online.) The initiative has now been opened up to all three campuses. “At the end of the first meeting, students talked about leaving with their heads held higher, and about feeling empowered and feeling seen,” says Rhonda McEwen, an associate professor of new media, and the special adviser on anti-racism and equity at U of T Mississauga.

AS THE UNIVERSITY TACKLES issues of racism and equity, it is crucial that Black voices be heard. We must be able to share our experiences of exclusion, of microaggressions, and of pain and violence. Our white colleagues need to listen, and as Hashmani reminds me, everyone must help dismantle barriers. “The onus doesn’t only lie with the Black community,” she says. “All of us create this system; we all need to take responsibility for it.”

A statement someone made at the National Dialogues sticks with me. I think about it as I watch and engage with my non-Black colleagues in the work of allyship and dismantling harmful policies and systems. It stays with me as I engage in sessions hosted by leaders in equity, diversity and inclusion. It stays with me as I navigate religious spaces and family dynamics where unlearning internalized systems of oppression continues. It stays with me as some organizations remain silent – which in itself is harmful.

The statement is simple: “Action inspires hope.”

Action is happening at U of T. There could be some who don’t like the changes, but as Voisin says, “The eggs can’t be unscrambled. There is no going back.”