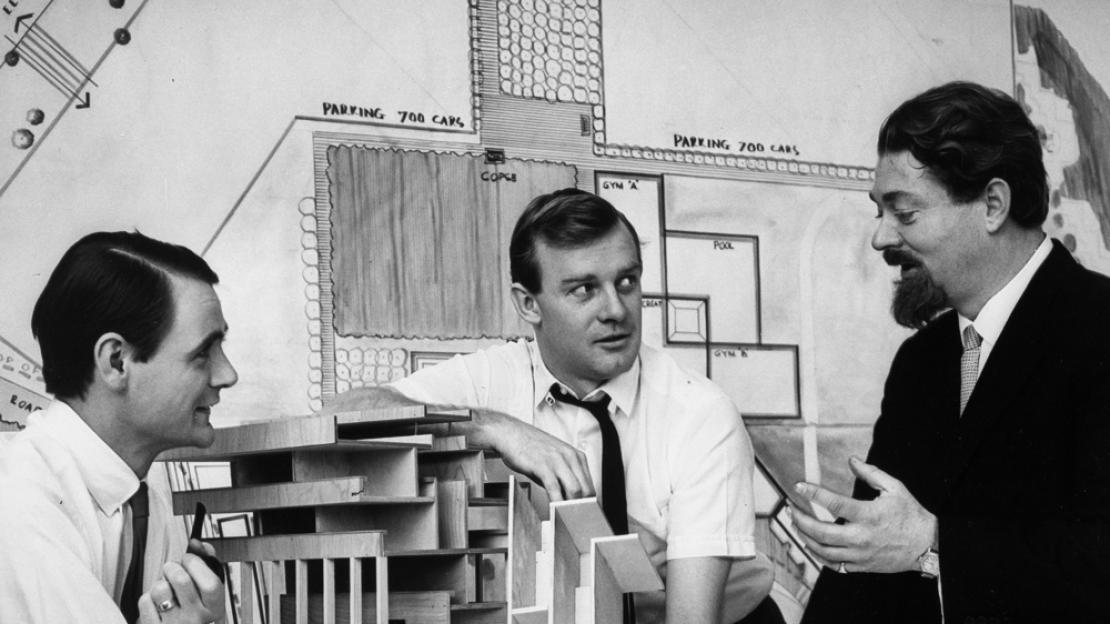

John Andrews, the Australian architect who designed two iconic Canadian buildings — including one at U of T Scarborough — died last week at the age of 88.

Andrews was 29 when he was hired by the University of Toronto to design a building for what was then Scarborough College. UTSC's first building, known today as the Science and Humanities Wing (sometimes referred to as the Andrews Building) attracted world-wide attention when it first opened to students in 1966. It was widely considered an innovative project and celebrated by architecture critics, even making the cover of Time magazine in January 1967.

The building's unique architecture has been the backdrop for many tv and film shoots over the years, most notably Total Recall, The Shape of Water, Resident Evil, and a music video for Scarborough's own The Weeknd.

Andrews would later go on to design Toronto's iconic CN Tower.

Born in Sydney, Australia in 1933, Andrews completed his bachelor of architecture at Sydney University, and in 1957 entered the masters of architecture program at Harvard University. He went on to establish John Andrews Architects in Toronto in the 1960s while working as a part-time lecturer at U of T. He also designed buildings for the University of Guelph, Brock University and the University of Western Ontario.

The following is an excerpt from a 2014 UTSC Commons article that describes how Andrews felt about the term "brutalism" and the story behind how he designed UTSC's original campus building.

Atop the valley

If you've read anything about the architecture of UTSC's first building, the Science and Humanities Wing, you’ve probably seen its style described as “brutalist,” a movement that saw the construction of such large, all-concrete structures from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Just don’t use the term when you talk to John Andrews, the man who in 1964 designed what was then Scarborough College.

“I object quite strongly to the word ‘brutalist’,” says the 80-year-old architect from his home in Orange, Australia. “It isn’t brutal. Scarborough College is a very human building.”

Andrews was just 29 and a practising architect, as well as a part-time U of T architecture professor, when President Claude Bissell asked him to oversee design of a new campus on 202 acres of land the university had just purchased in Scarborough’s Highland Creek Valley.

Bissell expected him to build in the valley. The first thing Andrews did was consult climatologist Fred Watts, a geographer and founding member of the college.

“His information turned out to be incredibly important, because as he pointed out, the buildings in the bottom of the valley had a very late sunrise and an early sunset,” he says.

So the university agreed to locate the campus at the top of the valley, overlooking Highland Creek. Now, what to build? Again, weather played a key role.

“When you look at the university year in Toronto, it’s bloody cold for most of it,” says Andrews. “There was no doubt in my mind that this shouldn’t be a series of isolated building blocks where you had to trudge through the snow to get from Science to Humanities. It ought to be one continuous building. Once you took your coat off, it could stay off.”

That led Andrews to create what he calls the pedestrian circulation streets along the ground floors of each wing, allowing students to move easily to classrooms, stairs, elevators and to the Meeting Place in the middle. And to build it all in the allotted time—little more than a year—he designed the massive structure using poured concrete. “It was the only material that was capable of forming the continuous floors and the continuous walls.”

Practicality was important, but the design also had an artistic purpose for Andrews. “I was expressing the continuity of teaching—that everything was connected.”

The building opened in early 1966 to international accolades for its architecture. Andrews went on to design Toronto’s CN Tower and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, both in concrete, before returning to Australia in 1969.

Still consulting, he concedes that brutalism is a word “I’ve been tagged with.”

What would he prefer?

“If there was such a word, ‘appropriatism.’ What I’m always trying to do is find the logical answer to things, and at the time when I was, if you like, being brutal, it was the logical answer.”

By Berton Woodword