Face down in the sand, the three-year-old almost looked at peace, head tilted to one side and auburn hair matted against his forehead. As if sleeping deeply. As if a touch from one of the rescue workers on the Turkish beach that warm, late summer morning of September 2, 2015, might be enough to wake him up.

Of course, it was not.

Alan Al-Kurdi’s death — and, more specifically, its image: the photo that went viral and circled the world — set something extraordinary into motion. In Canada, people opened their hearts. Rarely, in either war or peace, has a single image had such an impact.

The plight of people in war-torn Syria was no longer relegated to the back pages of newspapers. The media devoted prime time and space to the Al-Kurdi story. Alan’s mother and his five-year-old brother, Ghalib, had also drowned on the 40-minute boat ride to the Greek island of Kos. There was an aunt in Vancouver, reporters learned. The family wanted to come to Canada, but their application had been turned down.

With a November election approaching, the tragedy became an election issue. Each of the three major parties promised to bring in large numbers of refugees. The Conservatives said 10,000 over three years. The NDP said 10,000 by the end of the year and 9,000 annually after that. Both were trumped by the Liberals’ promise of 25,000 by January 1st.

“I can’t even imagine what that father is going through right now,” Trudeau said. “This is something that goes beyond politics.”

Clearly, the Liberals had an ear to the ground, for those words reflected the public consciousness. In numbers not seen since the influx of Vietnamese ‘boat people’ in the 1970s, Syrians began to arrive at our borders. In spring 2015, before the Alan Al-Kurdi photo, there were 1,300 Syrians who had resettled in Canada since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011. Five months after the photo, there were 26,166 — 11,000 of them privately sponsored.

“I saw the photo and cried,” says Lisa Morgan, a radio DJ with 107.5 Kool FM. Morgan lives in New Tecumseth, Ontario, a town of 27,000, just north of Toronto. “I said to my husband, ‘something has to be done. We need to sponsor some refugees.’ And he said, ‘but it’s expensive.’ And I said, ‘let’s ask the community.’”

Working with others from her town, including four churches, Morgan formed Refugee South Simcoe, which to date has sponsored three families, two of them from Syria — a total of 12 people. These families were resettled in and around New Tecumseth and the nearby Alliston area.

Unfortunately, though, in the logistics of private sponsorship lie the seeds of potential future problems. So explains Steven Farber, a professor in the Department of Human Geography at U of T Scarborough. Private sponsorship does not have a similar vetting process to government sponsorship. For government-sponsored refugees, the area chosen for resettlement must meet Ottawa’s list of criteria. Only neighbourhoods with support services — such as transportation, medical facilities and refugee-specific social services — get the go-ahead. For privately sponsored refugees, the location is usually evaluated based on the sponsor’s needs — e.g., affordability and convenience — regardless of whether it offers sufficient newcomer services.

Based on existing academic literature, Farber believed this approach could be problematic. So he and his research team surveyed 60 men and women, mainly from Syria, in the region of Durham, Ontario, and conducted four focus groups sessions, each with eight to 10 participants. The team worked with researchers from Community Development Council Durham (CDCD), McMaster University and Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

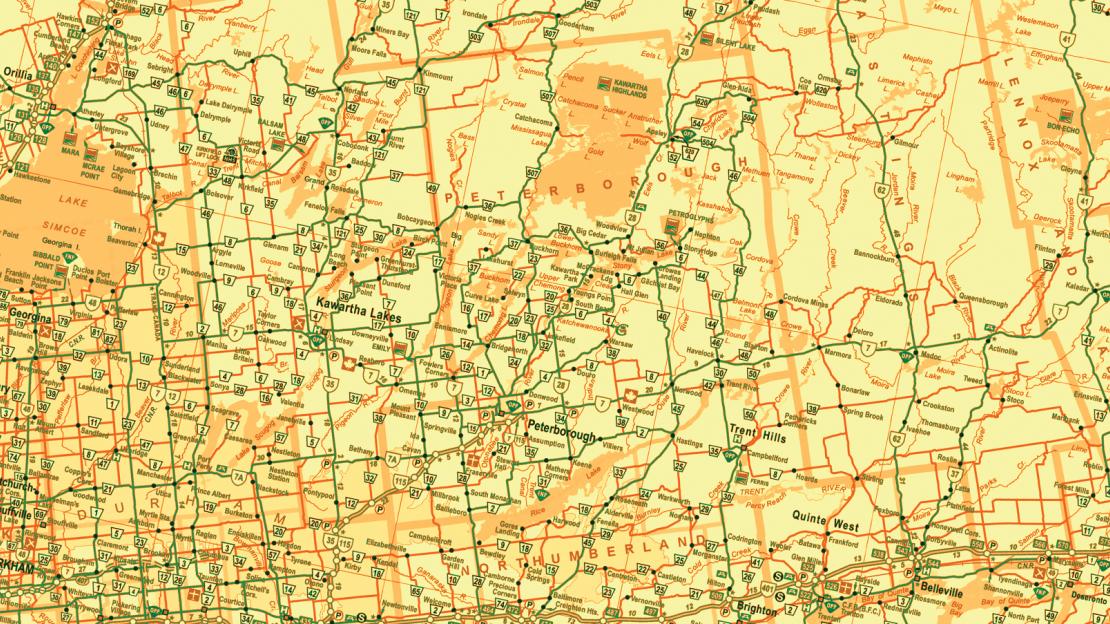

Their research findings, which explored the problem and also looked toward solutions, were published in the Journal of Transport Geography. The findings showed that Durham was well-suited as a site for research on refugees and transportation challenges, due to its size and lack of public transit. “It is very difficult to get from one side of Durham to the other,” says co-author and CDCD researcher Anika Mifsud. She says it’s “actually quicker to take a train into Toronto, and then get public transport back out to Durham again.”

Of the people surveyed, 84 per cent did not own a vehicle, but wanted to. Sixty-two per cent of respondents said the combination of lack of public transport and no car had worsened their sense of loneliness. Fifty-seven per cent said it increased their sense of sadness.

In the focus groups, the researchers could unpack what was actually going on, seeing and understanding the stories behind the statistics. What emerged was a sense of isolation. One participant said, “My family and I are Muslim; sometimes we need halal stuff. I can only get them from Scarborough; sometimes it takes me up to five hours to reach Scarborough with the transportation.”

A typical story that researchers heard: “At my children’s school there are activities, for both of my kids, but I don’t have time; there is no time; I have to walk and it takes me time to get there; there is no opportunity to participate; it is because of the transportation.”

Social exclusion has already been well documented in academic literature, particularly in studies of elderly Canadians and Canadians living in poverty. These groups are less likely to engage in activities outside the home, either because of the cost, a lack of time or energy, or a combination of the three. And this can lead to mental health challenges.

Mifsud says the situation can be even worse for people arriving from a war-torn country. Anything that reminds an immigrant of home — be it a specific food, such as the Syrian yalanji (vegetarian stuffed grape leaves); an activity, such as a service in a mosque; or bantering in a shop in Arabic — can provide a sense of belonging and familiarity. This can help the person cope with a sense of loss. And, in the case of war refugees, it can help them cope with memories of war and violence.

Mifsud explains that community, culture and connection are crucial in helping people overcome the tragedy of war — so any form of social exclusion can be problematic. “Those linkages to their home country can be fragmented and tenuous because of the violence. And so they need more reminders of those cultural and ethnic links through food, language, people or other cultural products."

This research does not surprise Dareen Yousef, 40. She, her husband and their three daughters (now 13, 12 and eight) used to live in Damascus. They belong to a small Islamic sect called Ahmadiyya. Founded in India in 1889, Ahmadiyya emphasizes peace over violence and tolerance over extremism, and has strongly and publicly denounced ISIS.

When the war broke out, Yousef was a stay-at-home mother and her husband was working as an accountant. In 2011, as violence escalated, the family flew to Jordan to visit her parents — and while they were there, their home in Damascus was bombed.

Being Palestinians, the couple weren’t allowed to work in Jordan, so they moved to Ghana. There too, their Palestinian status created obstacles to finding work. They lived in an Ahmadiyya compound in Ghana’s capital, Accra, barely eking out a living. They felt trapped. “We were in Ghana looking to get out somewhere. We got an application from an aid organization and it happened! I didn’t choose Canada,” says Yousef. “Canada chose me.”

The family moved to Mitchell, Ontario, 20 km northwest of Stratford, because that’s where their sponsor lived. Yousef likes Mitchell, an agricultural community of 4,500, because it’s green and quiet, and the people are friendly. But the downside is the absence of Syrian food or ingredients. The nearest places to purchase them are London and Kitchener, and, without a car or public transit, the only way to get there is via cab. This is expensive — $200 for a round trip to London. “It was very hard at the beginning,” she says. “I was very lonely. There was too much different.”

“Our rural clients are really struggling,” says Mifsud. Both men and women are impacted by a lack of affordable transportation, but women tend to feel it most, perhaps because they’re often trying to organize the whole family’s daily needs and schedules. They’re also the ones most likely to be isolated in the home.

Dima Aldahouk, 33, can relate. In Syria, she lived in Harasta, a suburb of Damascus, and was an accountant in a yogurt factory. She and her husband, Ousama Juha, both use wheelchairs — he because of polio, and she because of a car accident — and both are accomplished athletes. He won the gold medal in wheelchair powerlifting in an Egypt world cup competition in 2005, and represented Syria in wheelchair basketball in 2014. She won the bronze medal at an international world cup in Jordan in 2012.

After their house was bombed, the couple fled Syria. They arrived in Canada on March 15, 2017. In Syria, they lived rich and full lives. But here in Canada, they have struggled.

After living in Hamilton for more than a year, neither has been able to find work. Not having a car affects their ability to do almost anything — e.g., attend language classes, have a social life, buy Syrian foods, find a job. And “when the snow comes,” Aldahouk says, “it’s hard to be in a wheelchair. Sometimes, I can’t leave the house because I have two kids. [The youngest, age four, has Down syndrome.] I can’t deal with the kids with my legs. Sometimes I’m scared. So I just stay home.”

Aldahouk’s story shows the real danger inherent in the lack of accessible and affordable transportation. It also shows that the problem isn’t only rural; it also exists in some city neighbourhoods.

Without immediate relief, resettlement problems can deepen and become entrenched. Social isolation affects the ability and speed of language learning, which impedes the ability to find work, which leads to a lack of confidence, which further impedes the ability to find work. And so the vicious circle deepens. If people can’t engage with their community and the larger society, it’s bad for their mental health, Steven Farber says, and “in the long run, that entrenches poverty. Transport impacts people’s lives in a visceral way.”

The good news, according to Farber and Mifsud’s research, is that solutions exist — and are quite doable: Develop guidelines about appropriate neighbourhoods for privately sponsored refugees, or — perhaps easier — just subsidize transportation costs. For example, says Farber, give people cab or Uber money, or arrange carpooling. “The solutions to these problems are not very complicated, and they do need to be implemented.”

For now, the households of Aldahouk and Yousef are trying to save up to buy cars. It isn’t easy.

After a year of job searching, Yousef is now a dietary aid in a nursing home and her husband is working as a painter. Still, with three children, life is expensive. “I don’t know how long it’s going to be to afford a car,” she says. “I wish. I’m trying. Sometimes you feel down. But you have to tell yourself to get up and focus on the good things.”

Getting around in the suburbs can be difficult. In Durham region, it’s actually quicker to take a train into Toronto, and then take transit back out to Durham again

Transport impacts people’s lives in a visceral way, says Farber. If people can’t engage with their community and the larger society, it’s bad for their mental health and in the long run entrenches poverty