For decades, the environment in the eastern Hudson Bay region of the Canadian Arctic has been changing, yet very little direct environmental data has been collected from Arctic regions in Canada.

“A lot of the observations that people living here have made are the only consistent and reliable observations we have about changes,” says Megan Sheremata, a PhD candidate in the Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences at U of T Scarborough.

“It’s really valuable to have those out there and published.”

For her doctoral research, Sheremata is collaborating with four Inuit communities in eastern Hudson Bay: Kuujjuaraapik; Umiujaq; Inukjuak of Nunavik (the Inuit territory of Northern Quebec) and Sanikiluaq, on the Belcher Islands of Nunavut.

Her work, developed in partnership with the Arctic Eider Society, centres on engaging with Inuit knowledge of environmental change. Her goal is to work to mobilize Inuit knowledge so policy-makers and researchers can better support Inuit priorities in the region.

“Environmental change happens to communities, so you really need community perspectives to shape how meaningful policy responses are developed,” Sheremata says. “There is a lot of robustness to Inuit knowledge, because Inuit rely on it for food security, community wellbeing and survival.”

Her interviews with elders and younger hunters focus on Inuit knowledge of environmental changes since the 1970s, in the wake of the James Bay Project.

communities Observe decades of change

In 1971, the Quebec government and Hydro-Quebec began construction of what remains one of the largest hydroelectricity complexes in the world. Numerous rivers were diverted into an immense system of reservoirs, massively expanding the La Grande River watershed in northern Quebec.

This created a larger, more persistent plume of freshwater flowing from the La Grande River into the saltwater systems of James Bay and eastern Hudson Bay. Seasonal freshening of saltwater in the region always occurred in spring. Now, the deluge of freshwater happens during winter.

The result is less saline surface waters, which significantly impacts sea ice. And it occurs just when tuva (the Inuktitut term for peak sea ice conditions) occurs. Tuva is critical for safe hunting in winter, when wildlife populations are scarce.

“Peoples’ ability to move across the ice has been totally transformed,” Sheremata says. “The fact that you can’t access so many locations today is very significant to hunters, and for food security in the community because a huge part of Inuit culture is sharing the food that they catch.”

By the 1980s, Inuit began noticing many changes in the water, land, weather, ice and wildlife. Since the 1990s, climate change has exacerbated the impacts of hydroelectricity, and created new ones — for example, sea ice has become much thinner and conditions are harder to predict by hunters.

Sheremata is identifying Inuit knowledge-based indicators of changes in salinity, sea ice, and wildlife noted by Inuit hunters over the years.

“Inuit knowledge gives you another opportunity for in-depth understanding, and for many physical scientists and policy-makers, the context provided by Inuit knowledge is becoming recognized as really important,” she says.

Research built around community collaboration

Sheremata says historically, Inuit perspectives have been sought and used primarily when they have fit nicely within existing research, an approach she says can obscure Inuit observations of environmental change and why they are significant.

Instead, Sheremata wants to give space for Inuit knowledge to frame our understanding. This has meant making ongoing efforts to collaborate with communities throughout the research process. Interviews have been designed to be loosely structured to allow her research questions to change when appropriate.

One of her goals is to understand how Inuit want their knowledge to be shared. She has worked toward this by conducting collaborative analysis workshops in communities.

“When you don’t do that, when you interview people as a one-time thing, you really miss out on an opportunity to develop a nuanced understanding of what you want to know,” says Sheremata, who designed the co-analysis workshops to ensure the themes she has focused on are relevant to communities and are being interpreted accurately.

These workshops also help ensure participants can meaningfully give informed consent to the sharing of their knowledge. The more they are involved in the project at all stages, Sheremata says, the more informed their consent becomes.

One of the greatest challenges identified by local hunting organizations involved in this project is that young people are losing their connection to Inuit knowledge due to the ongoing impacts of colonialism, Sheremata says.

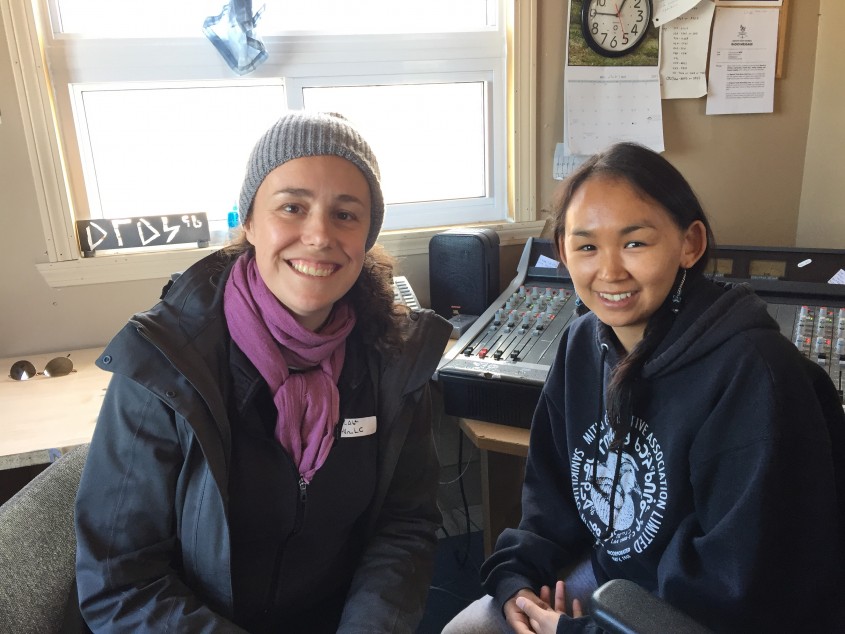

That is why youth ages 18 to 30 from each community were involved as research assistants during workshops and interviews. Their involvement was aimed at fostering connections between youth and elders. They helped record interviews and played a key role in ensuring translations and interpretations were as accurate as possible.

Sheremata says the Inuit knowledge is closely connected to the Inuktitut language. However, Inuit are very concerned about the erosion of Inuktitut among younger generations.

Many of the elders Sheremata spoke to have hope for solutions, and most expressed the belief that their communities can adapt and overcome the changes to the environment.

“Almost every elder I talked to has said that as long as young people can get on the land and hunt with elders, environmental change is surmountable.”